Back in Friuli Venezia Giulia, a region in Italy that is close to my heart, I took a long weekend to catch up with a few long due visits.

One of the (no longer) hidden pearls from the region, are the macerated white wines (aka orange wines). Those have been steadily growing in quality, technique and relevance in the region in this last decade.

Legends like Gravner, opened the way to many other producers to explore the complexities of a white wine produced as red one.

In a nutshell, to produce white macerate wines, the grapes are gently pressed with their skins. Those are left in contact with the must from a few hours to several weeks. This process lends body, length and depth to the wine. The color is built over darker hues of yellow, which can get more intense depending on the maceration time. The process also builds a characteristic range of aromas that includes bees wax, almonds, terracotta and orange peel.

Macerated white wines are one of a kind. I won’t tell you if good or bad, since taste is as individual as fingerprints. However, I would suggest that on the first time you try it, keep an open mind, be slow on judging and preferably, be comfortably sitting.

Meeting Roberto Picech

I started the journey from Trieste up to Collio early in the morning, with Sara, an oenologist friend of mine. It was one of those incredibly hot days from this summer and moving up the hills mildly brought some freshness to the air.

Among the meetings we had scheduled for the day, Picech was one I have been waiting for a while to connect with.

We were received by Roberto Picech, owner and wine maker of Picech wines, and his dog. Both welcoming us warmly, each one in their own ways.

As we began our chat, we head out for a walk around the plots of the pretty vineyard.

Picech started a while back to implement organic practices, which have now reached the whole vineyard. Flowers and grass grow freely along side the vines.

Nature has historically been generous with the region, but the weather has been playing challenging cards lately. Super hot summers are making it trickier to align the maturation curves of the grapes. As a contrast, hail has been hitting hard the Friulano vines for two years. With an attentive eye, we could see sporadic bruises on the branches from the ice, giving clues on the story behind the losses from the last vintages.

Coming back to the house, our canine friend was there waiting for us. She welcomed us back with such happiness that it felt we were away for days, instead of minutes.

A vespa by the door of the location entrance reminded us that were in Italian territory.

We were at home.

Meeting the Picech wines

A particular aspect of wine tasting that I enjoy is the build up of expectations, as you move up in the complexity of the bottles.

Roberto first presented us with his classic wines from the most recent vintage on Friulano, Malvasia and Pinot Bianco.

Still wild and hyper active in the glass, waiting for a bit of aging to calm them down a bit and lend the stability that only time can give. Potent, with a lot of warmth in alcohol, recalling the hot summers in the region. All well incorporated in the body, creating precision in the experience.

As the sun begins to slowly set and we were closing our chat around the classic line, Roberto got things ready for the next act. He slowly stood up, cleaned a bit the table with a piece of cloth, reorganized the glasses and asked whether we could call the main actresses to the stage.

Athena

Athena, was named as of his daughter. An interpretation of Friulano through the point of view of a white maceration. Before going to lengthy descriptions or running technical evaluations in my head, the first sip just brought a smile to my face. The descriptors of Friulano are there but in a different, playful, bulkier and unapologetic way.

Friulano destemmed grapes, macerated for 16 days in large barrels (25 hl), without controlling for temperature and without using selected yeast. After pressing, the wine rests in large barrels for 18 months.

Intense on the nose, with opening on white peaches, acacia flowers, grapefruit, bees wax, green almonds and a minor but pleasant resinated note.

Intense and warm on the palate, the tannins play their role in resonance with the other elements of the structure of the wine. They bring tension and body to sustain a great level of complexity in the structure.

Jelka

Named after his mom, Jelka brings up the roots of the region. A blend of three indigenous grapes from Friuli: Ribolla Gialla, Friulano and Malvasia. The age of the producing vines range from 15 to over 50 years old. You can feel that the age of the vines has landed focus and concentration to the results.

Friulano grapes are destemmed and macerated for 15 days in large barrels, aging for 12 months. Ribolla Gialla and Malvasia are fermented normally and rest for 12 months in tonneau. The blend of the three wines is then brought to concrete vats, and rest there for about 3 years. Jelka, doesn’t reach the shelves before 5 years after the harvest.

Intense and complex on the palate. Balance sustained from the attack of the wine to the fading of persistence. The roundness in the palate is rich, but the acidity makes a statement in the structure bringing brightness, freshness and cleaning to the finish – which was really interesting to notice considering the work in concrete which brings the pH a bit up and the age of 5 years after the harvest. Great depth, which kept on opening by the minute. White flowers, lemon zest, candied orange peel, wet slate, claypot, cedar and cloves.

My definition of elegance in wine.

My thoughts on Picech wines

Talking with Roberto, reassures you of the pleasure of sharing great wine in great company.

Great wines are transparent to the personality of the wine maker. That is a true statement for Picech. Strength, warmth, unapolegetic. Yet, patient, elegant and with complexity and depth to create gravity in the glass.

Picech wines tell about the story of Collio, of Friuli. Looking into the past and creating space for the vibrancy of indigenous grapes, while aiming into the future and constantly iterating on new ways to improve their expression.

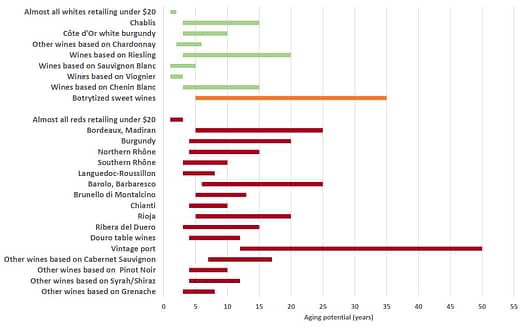

Potent wines built to age, and that know how to communicate strength and complexity with elegance.

For me, one of the ambassadors for the style in Friuli.