“Wines from France don’t give as much headache as the ones from the US”. That’s how a conversation between a couple of friends started last week during visit to a wine store I enjoy visiting. The argument was based on the belief that old world wines don’t have as much added sulfites as new world ones.

I thought about sharing some thoughts on that, but focusing on the reason being of that discussion: are the sulfites to blame for the wine headache?

You might have heard from the wine passionate crew that wine is a living thing and ever evolving. I won’t disagree. That is true for me both on the philosophical and on the physico-chemical side of it.

What are sulfites and why they are added to wine?

Sulfites, also known as Sulphur dioxide (or SO2), are used in the wine making process for its antioxidant and antibacterial properties. It’s an important component to improve the lifetime of the wine.

Wine is trying hard to become vinegar while resting inside the bottle. It is always evolving in that direction and we have been creating and improving processes over time to slow down this cycle. Holding longer the stage that we all enjoy between grape juice and salad seasoning.

Every time we open a bottle of wine the taste will be unique to that particular moment in its life cycle. Catching and savoring the wine at the right point of its evolution curve is where the magic happens.

Over time we have discovered several tweaks on production and storage to help preserving the wine. The dark color of the bottle to protect it from light. The seal of the bottle with a cork, to allow just enough oxygen inside to sustain the aging. Special care during the storage with the humidity of the environment, horizontal position of the bottle, swings of temperature, adequate levels of acidity to allow aging and… sulfites.

Are organic wines free of sulfites?

Sulfites naturally occur in wine at less than 10ppm (parts per million), generated by the yeast during the fermentation process. It’s a choice of the winemaker to further add sulfites, mainly aiming to avoid spoilage. In the EU the maximum levels of sulfites that a wine can contain are 160 ppm for red wine, 210 ppm for white wine and 400 ppm for sweet wines. Quite similar levels apply in the US, Australia and around the world. In reality the actual levels are much lower, with many dry red wines having around 100 ppm.

There are very few winemakers who produce wines without adding sulfites. In the US, to use the term “organic wine”, it means that no additional sulfites were added. These are unusual because the wine is very perishable and often have uncommon aromas from the chemical compounds that are normally neutralized by the sulfites. In Europe organic wines are called “bio” but sulfites are allowed in production, but not in those exported to the US. The term “natural” winemaking is used in Europe for no-sulfite-added wines.

The addition of sulfites to wine is not a recent practice from the industry. In fact, the first use of sulfur compounds in wine seems to date back to the Greeks, over a 1000 years ago. They noticed that the wine contained in the amphorae that treated with resin and fire, to seal eventual cracks, lasted longer than the ones from non-treated amphorae. What happened was that the pitch on the inner walls of the amphorae resulting from the fire, were dissolving sulfites into the wine.

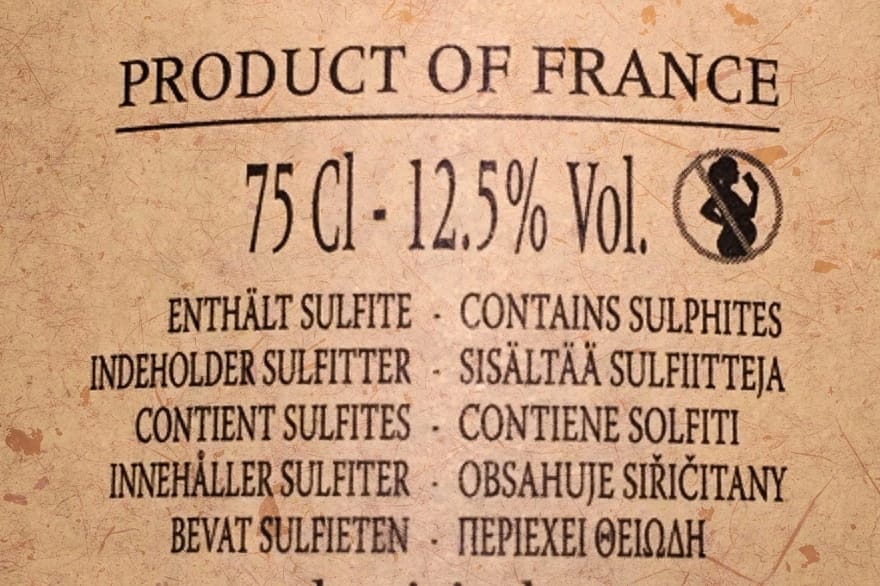

In the United States, wines bottled after mid-1987 must have a label stating that they contain sulfites if they contain more than 10ppm. In the European Union an equivalent regulation came in November 2005. Bottles of wine that contain over 10 mg/l sulfites are required to bear “contains sulfites” on the label. This does not differ whether sulfites are naturally occurring or added in the winemaking process.

Do sulfites cause headache?

The consumption of sulfites related to wine consumption is harmless. However, if you constantly get headaches after small doses of wine you might belong to the 1% of the population that presents intolerance to this chemical compound. The allergy to sulfites is found in really few cases of people that have an asthmatic record. If you would like to make a test, you can go to the closest supermarket and get a package of your preferred version of dried fruit (preferably raisins or apricots, which hold higher levels). They have about 10 times more sulfites than wine. Sulfites are also find in high concentrations in canned foods, potato chips, pickled vegetables, frozen juices and sodas. So, if you don’t get headaches from eating dried fruits most likely are not the sulfites that give you headache when you drink wine.

Red wines have generally less sulfites than white wines, and that is mainly due to the presence of tannins. This naturally occurring compound from the skin of the grapes has antibacterial and antioxidant properties. White wines don’t have tannins, hence cannot count on the natural help from the grape skin to improve its life time. This asks for an extra dose of sulfites during the production to make it up for it, respective to the red wines.

So, where does the dreaded wine hangover come from?

The research done so far tells us, nevertheless, that sulfites are probably not the reason of your wine headaches. The list of possibilities can get quite long and would include, of course, alcohol. This last one can induce dehydration which, among others, can increase the possibility of a headache.

Cheap and low-quality wine can be as well more prone to give you an unpleasant morning after. As seen in a previous post, if the wine price doesn’t reach the minimum threshold to insure an ok quality of grapes and a fair production process, there is a chance that more invasive methods were used. In order to correct the quality of a cheap and low-end wine the producer can add citric acid, concentrated grape juice, sugar and chemical preservatives beyond sulphur compounds. Besides, high quality wines contain less sulfites compared to low quality ones. This is simply because the latter, having a greater risk of unwanted fermentation, needs a higher level of added sulfites.

Ultimately, we are all looking for a wine that offers a long-lasting impression for the right reasons, and not because of a splitting headache. Moderation on the alcohol and better choices on the precedence of the wine are good bets for a happy morning after.