“Why should I let wine breath, if it has been locked inside the bottle for a few years already? Whatever was inside it’s probably dead by now” – that’s how the conversation started at the table.

There are two procedures that would help your wine breath: decanting and aerating (also known as carafing or oxygenation). Aeration, as the name suggests, puts the wine in touch with the air (mainly oxygen), allowing a better expression of its aromatic components. Decanting, helps separating eventual sediments in the wine before serving, with some oxygenation coming along with it.

Why should I decant wine?

Certain wines, particularly the aged ones, naturally develop an amount of sediments overtime. These sediments impact the texture of the wine, which can be distracting and even unpleasant. Removing these sediments will take you to a better tasting experience.

What about aeration?

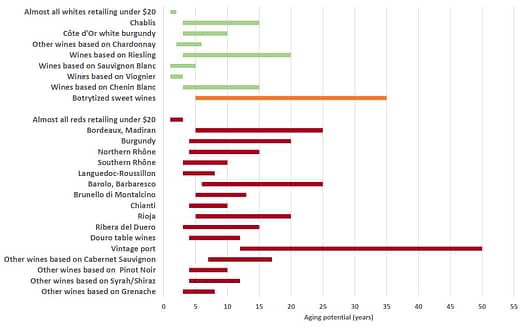

Every wine could benefit a bit from aeration. I would recommend aerating all wine, with a few exceptions and bit of care. As discussed in a previous post, a lot of details in the bottle and on the wine production methods are designed to slow down the aging process. One of them is to limit the contact with oxygen. Once the bottle is open and the wine gets in contact with an overwhelming amount oxygen, a series of chemical reactions are triggered. In older wines, for which the time has stopped for a while, this process happens much faster once the bottle is opened.

If done in the right measure, the aeration can:

- Help soothing some of the aggressive tannins in young wines. Don’t expect miracles, but it can soften a bit the texture of wines where tannins are still super active.

- Help brushing away off odours that occur in some wines, especially the ones with low content of sulfites. Unfortunately, if your wine is corked, aeration won’t help – actually it will make it worse.

- Help bringing up the layers of aromas that might have been trapped in the wine. As the oxygen triggers some chemical reactions, it induces volatilization of some aromatic components.

Aeration is a process that needs to be handled gently and with care. If the process is too aggressive or takes longer than required, it might damage the wine. You don’t want oxygenation turning into oxidation. Often in old wines, it takes minutes for us to notice it changing aromas and even colour inside the glass.

What wines should I aerate?

Not all wines have sediments, which would require some decanting. Nevertheless, most of the wines would benefit from some aeration. There is a component of personal preference to it. Experiment and have fun in the process. Despite this grey zone in the discussion about what wines should be aerated, much lead by personal preferences, there are some general guidelines worth mentioning.

Aerating Red Wines

To simplify, if we think about how much aeration a given varietal needs, based on its age, we could probably draw something like a bell curve.

Young wines need little aeration since they are still young and little stimulation is needed to have the aromas coming out. Aeration in young wines tends to help most on (slightly) soothing the more aggressive tannins. Again, it won’t do miracles but you should see a difference if you let a young Shiraz or Cabernet Sauvignon rest for an hour or so.

Mid aged wines are the ones that would benefit the most when it comes to bringing up dormant flavours. The time in the bottle can mask the aromas, especially some of the tertiary ones that you have been patiently waiting for.

Old wines need decanting because of possible sediment, but little aeration. We need extra care with them, as the wine structure might have become fragile over the years. In this case it is suggested to have the wine decanted just before serving.

Aerating White Wines

In general, white wines won’t benefit as much from aeration as the average red wine. Those that could possibly get a boost are the ones that got some aging (e.g. German Riesling) or heavier bodied ones that had some time in Oak (e.g. Californian Chardonnay) or that have a more complex aromatic structure you would like to bring up (e.g. Alsatian Gewürztraminer). If aerating, I would suggest to chill down the decanter, to a temperature that is 1-2 degrees lower than the one of the bottle, so that you don’t warm up the wine in the process.

Aerating Sparkling Wines

I am not a fan of oxygenating sparkling wines. It depends on the wine, and I believe those should be treated case by case. However, if you DO happen to have a nice vintage champagne, decanting can add an interesting edge to your experience (together with the use of a proper glass, please not a flute!).

A key thing is to have the decanter chilled down before aerating (as mentioned above for whites). Keep it in the fridge for a while so that it gets cold and you don’t warm up the champagne during the process. The second thing to keep in mind is to work gently and continuously when pouring the champagne. Gently let the champagne flow through the walls of the decanter and avoid having the champagne hitting the bottom at once. This way you avoid breaking the bubbles and having the champagne losing perlage once served in the glass. Don’t let it sit for too long. Keep the decanter covered and let it rest for 5-10 minutes. That should wake the vintage up a bit without stressing it out. Allowing you to enjoy the depth that a more complex sparkling deserves.

My thoughts on aeration

Aeration should be a process to gently wake up the wine and help it to rise and shine in the glass. It might have been sleeping for a long time in bottle, let’s be careful with the old ones. The timing on the process requires a bit of experience, probing and sensibility. If oxygenation is too much for the wine, it will let some of the aromas fade, and we’ll end up missing some of the stories that the wine would like to tell us.

Open the bottle, pour a sip in your glass and taste it. If you can’t feel the main notes (fruity, earthy, herbal…), or if it’s young and too tannic or if you spotted some off odours, let it sit for a bit in the decanter. Wait, try it again. Repeat. The right point is the one that matches with your preferences, expectations or curiosity (ok, also patience).

Personally, I avoid using a decanter whenever I can. If the time is short and you have a table of guests waiting, there are not many ways to scape and a decanter will be a good friend supporting you. However, whenever possible, I just open the bottle, serve the wine in the glass and enjoy it as it opens, the aromas develop and get wider in the glass. While the oxygenation happens slowly in the bottle, once opened, it allows you to taste each stage of wine waking up.

Pretty much like having the wine catching up with time, but that’s a show that you get a first seat to watch, interacting with it right there, in your glass.

Santé!